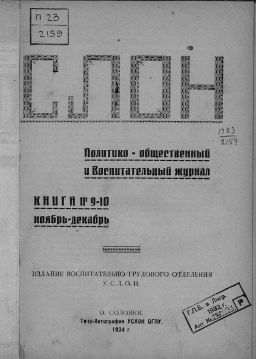

(Cover of the journal SLON, nos. 9-10 [November-December 1924])

Andrea Gullotta of the University of Glasgow recently published an important work of scholarship, Intellectual Life and Literature at Solovki 1923-1930: The Paris of the Northern Concentration Camps. Instead of explaining the book’s significance myself, I’ll link to two excellent reviews: Robert Chandler’s in the Financial Times and Lydia Roberts’s in LARB. Roberts is a graduate student at UCLA, who is herself working on the literature of the Gulag. As she writes: “The benefit of Gullotta’s book to researchers like me is that we can now, for the first time, point to an ideal primer on our subject, which makes the case for camp literature’s intrinsic value.”

Both she and Chandler cite striking pieces of verse composed under the most horrid conditions. Roberts offers her own subtle, sensitive translation of a poem by Boris Shiriaev (1889-1959), while Chandler writes: “Remarkable poems were published in Solovki. Among them is a cycle of parodies by Yuri Kazarnovsky, who spent four years in the camp in the late 1920s. Brilliantly recreating their voices, he imagines what Pushkin, Mayakovsky, Yesenin and other poets might have written had they, or their characters, been sent to the camp. An example is his version of the first lines of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin:

“My uncle is a man of honour.

When he ‘fell ill’, quite suddenly,

He had to leave his Moscow manor

And serve a term on Solovki.

A man of property, he’d led

The easy life of lords and peers.

You know what rhymes with peers? Ten years —

And that’s what his wise judges said!”

Chandler continues: “The deftness and boldness of these lines, which closely track the original, are easy to appreciate. What I would not have known, without Gullotta’s commentary, is that they are biographically accurate. In Onegin, the narrator’s uncle simply falls ill and dies; in reality, Pushkin’s uncle was imprisoned on Solovki from 1827 to 1832. From its first years, the monastery had doubled as a prison.”

The translation of Kazarnovsky’s blackly comic “Faux-negin” is mine. I based my version on Stanley Mitchell’s brilliant translation of the opening stanza of Pushkin’s masterpiece:

My uncle is a man of honour,

When in good earnest he fell ill,

He won respect by his demeanour

And found the role he best could fill.

Let others profit by his lesson,

But, oh my God, what desolation

To tend a sick man day and night

And not to venture from his sight!

What shameful cunning to be cheerful

With someone who is halfway dead,

To prop up pillows by his head,

To bring him medicine, looking tearful,

To sigh — while inwardly you think:

When will the devil let him sink?

You can read Kazarnovsky’s original, along with a selection of his other parodies, here.

Many thanks for this post about my book, and many thanks to the reviewers for appreciating my work! May I just add that the translations published in these reviews add a lot of quality to the texts I’ve taken into consideration than my book does? As a non-native English speaker, when translating the texts of the Solovki camp authors I’ve preferred to focus all my energies on conveying the right meaning without taking care of the form. Your translation and Roberts’ add more value to these texts. Thanks to you both

LikeLiked by 1 person

Andrea, I deeply appreciate your gracious response to the post and the reviews! But I assure you: all the thanks go to you. By unearthing and amplifying the voices of these gifted individuals, who suffered such pain in life and such unjust neglect in death, you’ve done what can only be described as sacred work.

LikeLike

Oh, thanks for these words. I can only say that during all these years I have approached the topic in the most respectful way, and I am happy to read that this has brought good results. Many thanks once again

LikeLiked by 1 person